Portugal Cork Forests

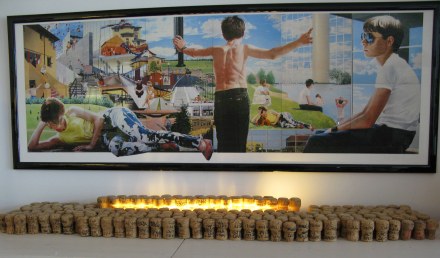

Cork - mostly from Portugal: a love affair and a tableau of great meals shared with friends

I must admit to being a cork snob.

I know there are such things as twist off wine bottle tops, but if you have any sense of occasion, there is nothing like the ritual and happy plup sound of a cork being extracted from a bottle of good wine.

Help me with my site, please take the below survey.

Happy times over good wines of all varieties are reflected in my home.

The

CD cabinet is lined with corks that bear the name of those with whom the wine

was enjoyed…and on one side a tiny note of admonition from my former boss that says:

'You are not fired – yet!'

The other small piece of paper pinned beneath it is my performance review. This is a man who believes if you cannot write it on something the size of two matchboxes, you have made it too complicated.

It’s a good rule. As Lin Yutang wisely wrote:

The wisdom of life

consists in the elimination of non-essentials.

For me, friendships are my essential life element. Therefore, the corks that punctuated happy times with my friends make a fitting decoration to my everyday life.

In the living room, a central shelf holds a growing collection of corks that previously kept in the bubbles with which many special times have been celebrated. Here are corks from French Champagne, good local German Sekt, Australian bubbles, Spanish Cava – and even two from the dreadful sweet bubbly (and to me, almost undrinkable), bought by friends in a gesture of kindness in Cuba.

Given my happy relationship with cork, on my list of things to see in the world were the cork plantations of Portugal.

I mistakenly thought all cork came from here. In fact, only about two thirds of the world’s cork – and arguably the best quality –comes from Portugal.

The cork oak requires good draining, silica-rich soils, good rainfall evenly distributed through the year but with good dry periods in-between, and a little humidity.

These conditions are uniquely found on the Atlantic coast of the Mediterranean. Therefore, other cork producing regions are in Spain, France, Italy, Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia.

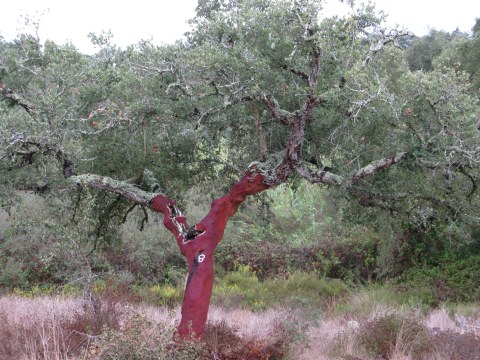

Cork forests north of Sagres, Portugal: once known as the 'end of the world' to Portuguese sea-faring explorers

Despite it being 'on my list', my cork forest discovery was an accidental one that followed discovery of remote coves and bays. It was more delightful for that.

We were staying in Sagres, known in the time of the great Portuguese exploratory mariners as the 'End of the World'.

Legend has it that there was once a marine school here, but this is refuted by archeologists. The astronomers whom Henry the Navigator appointed to join his fleet’s voyages of discovery were there only to plot the latitude and record the extent of his empire.

None-the-less, Portuguese navigators discovered new parts of a world just recently been found to not be flat. Thankfully for their sweethearts this meant the removal of their fear that their men would sailing off the world’s edge.

It is a habit of my childhood to take the lesser travelled path, so we set out just wandering along small back roads, north of Sagres.

The coastline is rugged and unspoiled by the packaged tourism blight of other parts of Portugal.

Storm surges have carved out bays.

Rocky cliffs plummet steeply to the sea.

There is 10,000km (6213 miles) of Europe behind you.

In the opposite direction, and half that distance away, is the next landfall.

We found a small fishing village and had a wonderful meal for less than 15 euros for two (in 2010). This included three generous courses and a fine bottle of local wine.

Having lingered pleasurably, we then wandered down to the beach.

Everything seemed coated in silver under the light filtered by a coastal storm.

Traces from the great Iberian Pyrite Belt reveal the residue from undersea volcanoes of ancient times.

Here there used to be Roman mines. It was a great transportation route for the gold, silver, copper, time, lead and iron found in the region. Sulphide ore and pyrite were also mined here.

The coastal

rocks are a wonderful mix of texture and type. The size of those thrown to shore gives some cue about the ocacsional ferocity of the sea.

Between them there are hardy flowers.

Raindrops rested on wide leaves to feed the sturdy beach plants.

Some hardy specimens were wedged into small sheltering spaces in the rock piles on the beach.

Leaving the coastline we wound inland and suddenly realised we were in a cork forest.

The cork forest isn’t laid out in plantation style – just a series of wild ranges punctuated by ancient trees.

The roads are excellent.

It was easy to see why harvesting was something of an individual tree affair and not some mass production machinery-led process.

I thought it rather a magical place.

Each tree in its own space on the hillside.

The driveway to this hillside farm house or casa de fazenda revealed the preferred soil of the cork oak.

Cork is the basis of an ecosystem that has been nurtured over centuries, with strict laws about only harvesting every nine years.

The plantation area grows by about 4% a year.

There are about 2.15 million hectares (5.3 million acres) of Portuguese cork plantation – and we were at its southernmost tip.

Cork is harvested with the care of individuals whose lifetimes can be divided by their visits to the same trees.

These harvesters are called 'extractors' and they have a delicate job. They need to be strong enough to penetrate the heavy bark with their sharp axes, yet never score the underlying core of the tree trunk. If they do, the tree will die.

The bark is cut into sections or 'planks'. These are then hand-carried to be loaded for transport. This style of cutis necessary because of the way the trees grow.

Unlike elsewhere in Portugal where Eucalyptus, English Oak, Pyrenean Oak, Aspen, Birch, Hazel, Fir and Pine grow in more orderly form, cork is individual and independent.

It grows in a more natural array.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons: Cazalla Montijano, Juan Carlos- This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

How cork trees grow: not in a tarditional 'forest'

The cork oak is a hardy, low tree of extreme longevity. In its 150 to 200 years of life, it will be stripped of its bark in nine year intervals – up to 18 times.

Extractor and cork oak therefore have a lifelong relationship of care on the one hand, and economic benefit on the other.

The number of the year of the last harvest is painted on the bark.

The cork trees look sculptural in the landscape.

It was not at all what I had thought of as a cork plantation.

Cork villages in Portugal

But obviously cork was a main staple of the economy.

It was stacked in yards…

…on the edge of small hamlets…

…beside beautiful white-washed homes…

…and equally colourful factories.

Here, the cork lay, some already stacked on pallets, waiting to be boiled.

The cork production process

There is a great series of photos that explain the production process here:

http://www.wineanorak.com/corks/howcorkismade.htm

Cork is a fascinating natural product. The cells contain 50% air.

The waxy material inside cork, Suberin –gives it its botanical name 'Quercus suber'.

Suberin is what gives cork its unique qualities. With its airtight cells and impermeable cell membrane, cork is:

- flexible

- buoyant

- elastic, able to be compressed

- waterproof

- has great resilience, lightness, and makes a great insulator.

Now not just used as a stopper, cork is being increasingly used in innovative ways in automotive and aerospace as well as in structural design. It has long been used:

- in musical instruments

- as an insulator in footwear

- a component in friction reducing machinery, and

- as a part of the paper pick-up mechanism in laser printers.

As part of the manufacturing process, cork is boiled. After one hour, the cells expand into a much tighter cell structure than its original wrinkled form.

In fact it was cork that gave us the word 'cell' for the smallest unit of a living thing.

In 1665 Robert Hook examined cork under a microscope. What he saw reminded him of the small rooms in which monks slept, so in his book Microgarphia he called this a 'cell'.

From the mountains we looked back towards the coast.

Here, was a new eucalyptus plantation – and it seemed sad to see just a lone cork tree.

Portuguese innovation: with cork a challenge for the future

I was glad of the innovation taking place to open the use of cork to wider markets than those of history.

Finding new uses for something requires freeing yourself from the limitations once accepted.

The Portuguese should be well placed to do this. In history they were great challengers of established wisdom on the nature of the world.

Cabral and Vasco de Gama brought India to the knowledge of Europe.

Through the great military genius of Afonso de Albuquerque, Portugal became the first global empire.

Albuquerque was the first European to sail into the Persian Gulf and proved to be just as able on land as administrator establishing India as a spice colony for Portugal.

Magellan was the first to circumnavigate the world – disproving the long-held myth of equatorial seas so close to the sun as to burn a man’s skin black on seas that boiled, and where ships caught fire.

Henry the Navigator – who never actually led any exploration but financed many – designed the new, lighter type of ship, the Caravel, that enabled fleets to go further, faster.

So I expect the Portuguese to create innovative and sustaining new markets for cork – the staple export product of a fragile economy.

Meanwhile, in the cork forests of Portugal, some ways of life remain eternal.

We suddenly rounded a corner to see this mule trap passing at a measured pace in the rain.

The Atlantic coast of Portugal is a place of discoveries.

Its small fishing harbours are tucked safely into inlets that keep the ferocious seas at bay.

The sea bringing moisture to the cork forests of Portugal

Atop Portugal’s coastal cliffs the silver of sunlight on grey seas accentuates the stark whitewash of fishermen’s houses.

The Atlantic coast of Portugal and its fringing cork forests have weathered many storms.

I was captivated by the beauty of this small corner of Portugal’s cork country.

In 'The Minotaur' Robert Camus wrote:

In order to understand the world,

one has to turn away from it on occasion

I was happy to have turned away from my world to that of Portugal’s cork country to refresh my soul.