Kerkouane

Ruins & Royalty

Kerkouane found by chance.

Chance: always honed by experience

The story is told that Georges Soumagne, archeologist and passionate fisherman, was sitting on the cliffs of Kerkouane when he noticed on the ground around him some broken pieces of black glazed pottery and what appeared to be bits of stucco.

Thinking these to represent pre-Roman artifacts, he alerted the Department of Antiquities and an archeological dig began.

That was in 1952, and within hours of beginning to dig, the finds began to accumulate.

Kerkouane is now a UNESCO World Heritage site, being 'the only example of a Phoenicio-Punic city to have survived'.

Pre-dating this discovery, in 1929 a local schoolteacher had discovered the necropolis, some 40 kilometres away from Kerkouane (almost 29 miles away).

Having plundered the site and sold off much of the better finds, the school teacher eventually found himself having to answer for the sudden wealth that was disproportionate to his means – and it was not until then that this site was officially documented and researched.

It may have been the knowledge of the site of the necropolis that heightened Monsieur Soumagne’s awareness.

Kerkouane slumbers still in the Tunisian sunshine, but is now no more than excavated ruins.

Kerkouane - the jewel over which fought Carthage and Rome

The three Punic wars between Carthage and Rome that took place between 264 B.C to 146 B.C. were a battle of power that originally stemmed from competing interests for domination of Sicily.

The Carthigians came from Pheonician stock (Roman word for Phoenicia being ‘Punicus’) and were an accomplished naval force.

The Romans were a land-based army.

For once the Romans found themselves at a disadvantage as a fighting force.

In the words of general George C Patton, whose legendary study of history enabled him to fight in Tunisia from a knowledge of the hardships, conditions, and opportunities of both the Carthigians and the Romans:

Never tell people how to do things.

Tell them what to do

and they will surprise you with their ingenuity.

In Rome, someone may have well said the same.

The problem was how to match a superior naval force.

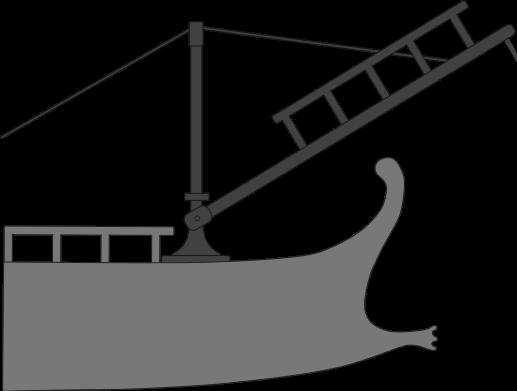

The result was the invention of the Roman Corvus, shown here in this diagram, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

This device was essentially a swinging bridge with a hooked spike on the end.

The spike was there so the boarding bridge held fast to the enemy ship, allowing the legionnaires to swarm across to engage in hand-to-hand combat.

It was first used – and very successfully - in early the Punic Wars, but in rough seas it proved useless. Its considerable weight at the prow of the Roman ships and subsequent compromise of stability is thought to have contributed to the massive losses of almost the entire fleet in a storm in 255 A.D. and again in 249 A.D.

My own experience of Kerkouane also involved arrival by sea and that crossing gave some indication of how troubled the sea can here. Having made the ocean crossing from Sardinia to Tunisia ahead of a predicted serious gale, the yacht on which we were sailing was tossed in Force 6 winds on what is called a 'confused' sea – one which seemed to have no direction, with waves crashing over us alternately from one direction or another.

In a black night during which it never stopped lashing with rain, keeping a two hour watch was an exercise in fortitude and concentration.

Leaving my watch I fell into a dead sleep almost instantly as soon as I reached the bunk - not even pausing to take off my life-jacket. I was very glad of the seaworthiness of the vessel as well as the competence of the owners, who had been sailing the English Channel since children and so were seasoned to the sort of uunexpected challenges that oceans can produce.

I can only imagine what a liability the estimated .9 of a metric tonne would make to navigability in such a sea. (That is about 1 US ton or .8 of an Inperial ton.)

Despite these liabilities, and despite the walled protection of Kerkouane, the Romans did eventually destroy it in 236 B.C. during the Punic Wars

Kerkouane - once synonymous

with the colour purple

Kerkouane was an important city. It was the production centre for the most valuable dye of the era: purple.

The colour purple was the rarest colour in the then known world.

Purple dye had been known to the Minoan civilization from about 1900 B.C. and at that time the biblical city of Canaan became a centre of production.

The Greek name for Canaan was Phoenicia – meaning “the land of the purple”.

The Murex shellfish and various other species of marine mollusks secrete a purple mucous - and legend has it that the discovery of the colour purple rests with Herakles (known to us as Hercules) and his dog – whose mouth turned purple after eating sea snails.

Herakles then had a cape dyed purple and presented it to King Phoenix who recognised the rarity of the colour and made the first proclamation that the colour was to be reserved only for royalty: Hence the phrase “Born to the purple”.

The purple dye was one of the most expensive commodities in the world and even Emperor Aurelian refused to allow his wife to buy a purple robe, as it was reputedly 'worth its weight in gold'.

Documentation of the ancient process reveals how intensive it was.

To secure 1.5 grams of pure dye required processing 12,000 shellfish. This gave sufficient dye just to colour the trim of a Roman garment.

As one wanders around the well laid out city, it's hard to imagine its former importance.

Washing away the purple

in a city of bathhouses, courtyards

and wide streets

The remains of wide streets and clustered town-houses are spread out under the Tunisian sunshine.

In the houses are various baths, still very much intact.

Ancient documents refer widely to the stench caused by the purple dye process – so perhaps the locals were obsessed with bathing the smell away, in private.

Kerkouane appears not that large as it stretches out before you, but in its busiest period, it apparently had a population of around 2,000 people.

The quality of the housing suggests that it was a wealthy city, with wide streets.

Houses had courtyards around a fountain that would have been the focal point.

Tours are now available, but we preferred to explore aided only by our imagination.

Discovered clues to life

in ancient Kerkouane

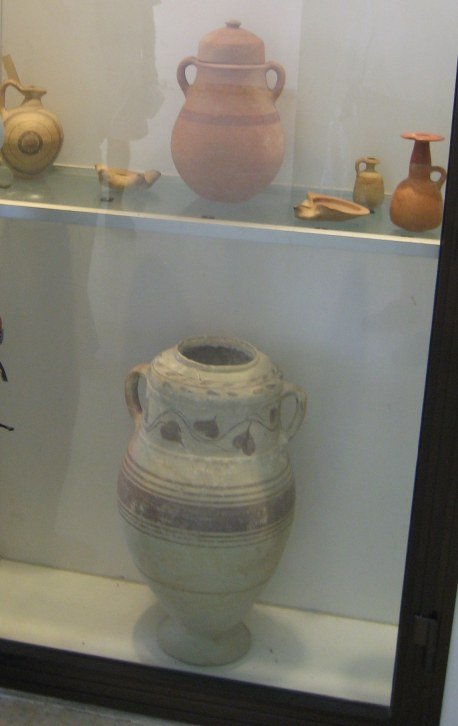

At the site there is a small museum (not open on Mondays) where some of the finds from the excavation of Kerkouane can be seen.

Clay vessels and tiles are artistically displayed there.

They are in remarkably good condition.

Charles Baudelaire said that:

Pure draughtsmen

are philosophers and dialecticians.

Colourists are epic poets.

Kerkouane, home of the world renowned Tyrian purple, shows its share of poetry as it lies before us under the hot Tunisian sun.

From the colour purple

to the synthetic chemical industry

It would not be until 1856 that the colour purple would be made synthetically.

The then eighteen year old William Henry Perkin (later to be knighted as Sir William) accidentally discovered an inexpensive purple dye while experimenting with synthetisation of quinine in his search for a commercial and reproducable remedy for malaria. Coming in the midst of the British Industrial Revolution, this discovery enabled the newly discovered manufacturing processes to bring the colour purple to the masses - and it made Sir Henry a very rich man.

Perkin’s discovery led him on to study how light is polarised by various organic compounds. These studies led to the development of the synthetic chemical industry.

In Kerkouane now, there are just shells left over as evidence of the early purple dye activities.

Good omens in Kerkouane

While we were looking for evidence of the dye-making, a native approached us very slowly: It was one of the small Tunisian tortoises with its very distinctive colouring.

Like the 'Hand of Fatima', a tortoise is considered very good luck, and is therefore a welcome visitor or resident of any Tunisian home.

To be graced by a Tunisian Tortoise crossing our path as we left the ruins of Kerkouane seemed a fortuitous omen for our onward sailing in Tunisian waters.

As William Shakespeare said:

Fortune brings in some boats

that are not steered.

More Tunisia pages here:

Hammamet